- DNA

29. 8. 2024

The Problem's Name is Genetic Burden

We have been breeding horses for hundreds and thousands of years. We choose among them the ones we prefer, while our preferences have understandably changed over time, especially in connection with their use. The horse population also developed significantly in terms of its size, the decline in the number of horses with the onset of the industrial revolution is particularly typical. And last but not least, breeding was quite often carried out within relatively small, mutually isolated populations. All of these factors have contributed significantly to the horses as we have them today.

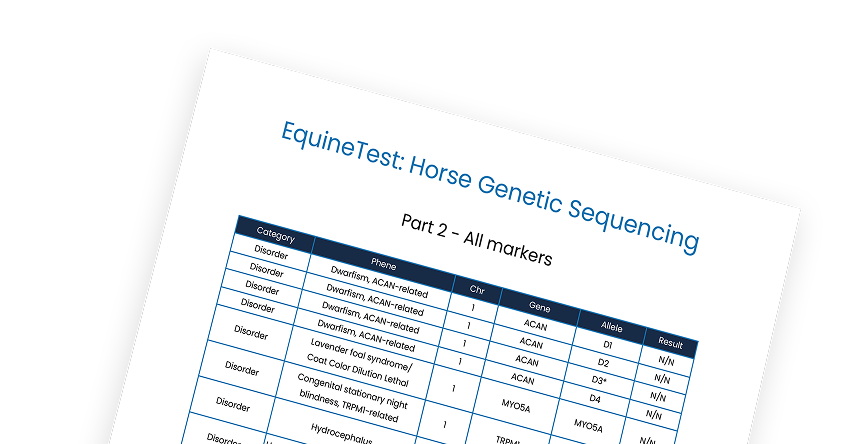

With the advent of genetic testing and especially in connection with the possibilities of analyzing entire horse genomes, such as EquineTest, efforts to identify causal mutations that are the cause of various diseases or, conversely, as a result of which a given individual has some desirable traits, have understandably intensified.

Unfortunately, we have to state that our ancestors messed us up a bit with their breeding interventions.

To date, genetic causes (mutations) are known for about 20% of genetic diseases in horses. And identifying the remaining 80% will be a challenge because the global horse population is not healthy. Not that all horses are sick, that's not the point. It is more about the fact that the horse is an animal that has not reproduced spontaneously, naturally, freely in nature without human intervention for a very long time. The horse population is thus far - and the question is how much - from the state it would be in if humans had not interfered in its development in any way.

Recently (in April 2024) a study has been published in Nature shedding some light on it. Authors are describing usage of whole genome sequencing strategy which in principle should allow rapid identification of rare disease causal variants in any organism if the target population has been carefully selected. It is quite a large study looking at 605 horses across 48 breeds which estimated the high frequencies of some previously reported disease variants.

It confirms that our ancestors have developed breeds with desirable traits, however, they have also decreased genetic diversity, thereby increasing the risk of inbreeding depression (i.e., the accumulation of deleterious variants and increasing homozygosity) leading to decreased average phenotypic performance. This has unfortunately resulted in numerous breeds with high incidences of deleterious disease traits. Mutations could - and did - become fixed that would not be maintained under normal circumstances.

The problem authors mainly focus on is the predicted genetic burden which refers to the presence of potentially deleterious genetic variants that a healthy individual carries. The researchers found that the median number of such variants per horse is 730. Authors demonstrate that this is 1.4–2.6-fold higher than in humans, and show that, as in humans, several previously suspected disease- and trait-associated variants are present at much higher frequencies than expected based on the published estimates of disease prevalence. This is consistent with the extreme historical population bottlenecks leading to smaller effective population sizes and selection for particular traits. Perhaps also possible errors due to a poorer quality of the horse reference genome which is a technical obstacle to be solved sooner or later.

Unfortunately, this means and confirms that horses are at even higher risk than humans of variant misclassification due to the relatively high number of predicted genetic burden variants found in otherwise healthy horses. Therefore, extensive consideration and validation of putative disease-causing variants, including the collection of genetic, informatic, and experimental data, is warranted before a conclusion about their causal effect is made.

Studies like this are never enough. They only confirm the need of more and more whole genome screening of horses and advocate for our approach of offering future reanalysis of EquineTest whole genome data sets.